Thinking 21st century art in the world from Niigata

Echigo-Tsumari Art Field - Official Web Magazine

Artwork / MVRDV

NOHBUTAI Snow-Land Agrarian Culturale Culture Centre, Matsudai

Artwork / MVRDV

NOHBUTAI Snow-Land Agrarian Culturale Culture Centre, Matsudai

Interview with Jacob van Rijs, MVRDV

On the 21st anniversary of NOHBUTAI Snow-Land Agrarian Culture Centre, Matsudai

Interviewer, editor and translator: Maeda Rei, Art Front Gallery

05 November 2024

The impact of the appearance of the pure white building “NOHBUTAI Snow-Land Agrarian Culturale Culture Centre, Matsudai” in the middle of rice paddies in 2003 is still vividly etched in many people’s memories. Today, the NOHBUTAI is one of the icons of Echigo-Tsumari and an important hub for the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, where a variety of activities take place. It was designed by MVRDV, a Rotterdam, Netherlands-based architecture and urban design practice founded in 1993, which is currently one of the world’s most creative architecture firms of more than 300 partners based in Rotterdam, Shanghai, Paris, Berlin, and New York.

On the occasion of the 21st anniversary of the NOHBUTAI, we present an interview with Jacob van Rijs, one of the founders of MVRDV and a key player in the NOHBUTAI project.

MVRDV/Jacob van Rijs ©Barbra Verbij

◀ NOHBUTAI Snow-Land Agrarian Culturale Culture Centre, Matsudai

It was built in 2003 in the Matsudai area and is one of the base facilities of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, and was the first artwork by MVRDV in Asia. The area is called the Matsudai NOHBUTAI Field Museum, with about 40 artworks scattered in and around the NOBUTAI building. (Photo by Nakamura Osamu)

Q: The 9th Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale was held this year, and many people visited theNOHBUTAI every day. Do you remember when Kitagawa Fram first visited your office in Rotterdam in 1999?

I think it was a Friday afternoon. We were still in our office at Schiehaven at the Rotterdam harbour, and at the time as a practice had no more than 20 people. Not expecting any appointments that afternoon, suddenly there was a knock at the door, and stood right in front of me was this Japanese gentleman, Kitagawa Fram. He didn’t speak so much English, but he was in town and a recommendation had been made to him to visit MVRDV. It was only later on that I found out via the TV that he was involved in the art world, was organising exhibitions, and was visiting Marina Abramović who at the time was based in Amsterdam. We also only later discovered that – I think – Fram’s brother-in-law (*Mr. Hara Hiroshi) is an architect who had made the recommendation.

He outlined the Echigo-Tsumari Triennale, the whole region, the arts, and the gallery, and that he was planning to build a kind of “base” for the Triennale itself. After he left we did some research, found out more about it, that the plans for the site were actually happening, and so we were really very lucky that we had this visit.

Luck also played another important role. Yoshimura Yasutaka, now a former architect of MVRDV, started working at our practice soon after. He picked up the communication with Fram, Art Front, and our collaborators in Japan, and he was very talented. He’d received a special grant from the Japanese government for high-potential architects, and he could nominate an office for which he would like to work. We were able to have him work with us for a very modest fee due to him having received this grant. So it was really perfect timing having Yasutaka in the office, being able to easily communicate with Fram and the gallery.

Q: The conditions for setting up NOHBUTAI were:

(i) To consider a pile of snow plows for russet trucks next to the Hoku-Hoku line.

(ii) To consider the high voltage line above the building

(iii) To incorporate a viewing platform for Kabakov’s “The Rice Fields”Furthermore, as many artworks as possible should be included in the architecture. You were selected as the architects who could meet these requirements.

How did you respond to them?

What ideas did you come up with for the architectural design? What were the most difficult and interesting aspects?

It’s a project that came from Art Front Gallery, but it’s also a form of municipal centre. Naturally it’s only every three years that the Triennale takes place and thus those interested in the Triennale visit, and then the atmosphere changes. So most of the time, the structure is wholly for the people who live there. And this is a rural area, a place with an aging population, which is a phenomenon already occurring in Japan already, but is taking place more quickly in these rural communities, something which was very visible with emptying villages and abandoned buildings.

They wanted to use culture as a tool for people from the cities to come to the area, discover it, for instance perhaps get a weekend house, but to find out what possibilities exist. And with Matsudai, it has a train station, so it was also doing somewhat better than other places.

So we went to see the town, and we presented the project, and indeed, it was to a room mostly filled with elderly people, with I think all of the men over 80 years of age. They were not especially worried about the design, the only kind of feedback that they gave was that you’re from a very different place, and so you must watch out for the climate and especially the snow. And the area has a fascinating continental climate. It’s very hot in the summer, and it has this humidity, which you certainly feel. Then it’s extremely cold in the winter, with huge snow falls, which adds weight to buildings, and then of course there’s also the risk of earthquakes.

Winter the NOHBUTAI

So structural conditions were exciting, to say the least, and we got a really good structural engineering form on board, Sasaki and Partners, who work with many well-known Japanese architects, including Sasaki Mutsuro who was like a guru. Our idea was that we needed to make this “lifted” building, to create both a snow-free place in winter and a shaded-placed in summer. So that was kind of fundamental to the story, it was not about design, it was that we make a building, we lift it up for you, and we make sure there’s no columns underneath so that you have a space for the neighbourhood. So the structure was important for the design development.

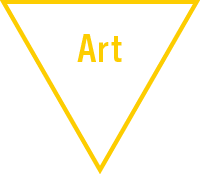

◀ Ilya&Emilia Kabakov “The Rice Fields”

At the time of production in 2000, before the construction of the NOHBUTAI. (Photo by ANZAÏ)

Q: When your proposal was first submitted in 2000, it was rejected by the Town of Matsudai because it had to be a Japanese-style building. When the same proposal was submitted in 2002, it was readily accepted. How did you feel about this process?

That was actually the meeting with the community I mentioned, and we were aware of the context, it was “super-local”, a very contextual design. We made these routes, including for the rice paddies. Likewise in the winter, when they dig out the snow with sculpted sides, and which you walk through like a corridor, we incorporated these corridors into the development of the staircases and their access points. So then they really understood that it was actually specifically being designed for them, and it wasn’t just some people from the Netherlands with a design like a UFO landing in their community. We told them that it would be cool to make it white because of the snow, and they said OK, and being white it’s also cooler in the summer, it made a lot of sense.

And then the structure was, of course, the big thing to do next. The engineer had envisioned a smart idea by making the leg-like bridges, they are like arches – like the structure of a bow – with a cable on the ground. And with being formed like a bow, this kind of tension can make the structure lighter. The second idea the engineer had was rather than using big beams for the big spans, he said I’ll make them smaller, but also higher. So you get these mountainous sculptures on the roof, which are actually structural elements laid out in a grid, and that rooftop expansion was a kind of “forcefield” of the structure, making the building itself cheaper because it required less steel to be used. Although some of these engineering elements happened after, they accepted the proposal after we explained what the story was, and they understood that it was quite respectful.

The NOHBUTAI from Matsudai station. Kusama Yayoi’s artwork “Tsumari in Bloom” can be seen in the foreground. (Photo by Nakamura Osamu)

The NOHBUTAI corridor *Josep Maria Martin “Museum of the Constellation NOHBUTAI of Matsudai”

Pilotis on the NOHBUTAI

Q: CLIP was in charge of the implementation design on the Japanese side, and Art Front Gallery coordinated with the artists. How did you find your collaboration with them?

The collaboration was really nice. Our co-architect was a firm called CLIP-architects based in Tokyo, who had worked with Art Front Gallery previously. Yoshimura Yoshitaka’s time with MVRDV was coming to an end, and it was really perfectly timed, because when he returned to Japan the project went into construction development. With Yoshitaka being in Tokyo, he was able to follow the construction, and for him it was also a great start to his own practice, despite not being the architect of record. He was something of a “middleman”, as he had a good overview about the project and the design.

In those days, everything was done by fax. In the morning we would receive all these faxes with sketches from them, which was very nice, and I believe it’s all in our archive. And it was all very detailed. When I was at OMA, Rem Koolhaas – who at the time was working in Fukuoka – would refer to how agendas and meetings were defined, and he was completely fascinated by the construction culture in Japan. It’s really much more respectful to the architect compared to many other countries, where the architect can be much more in “battle”, so to say. Contracts are much thinner, and meetings wouldn’t have any order in priority, whereas in the Netherlands we usually start with the most important, difficult part. These agendas were simply a list of items, and we wouldn’t move on until the previous point had been resolved, which means we could be talking about door handles for the toilets, and the next item could be the construction steps and the budget. This means meetings could be quite long, but at the end of those meetings, everything would be resolved and we could act quickly, because you come out with solutions.

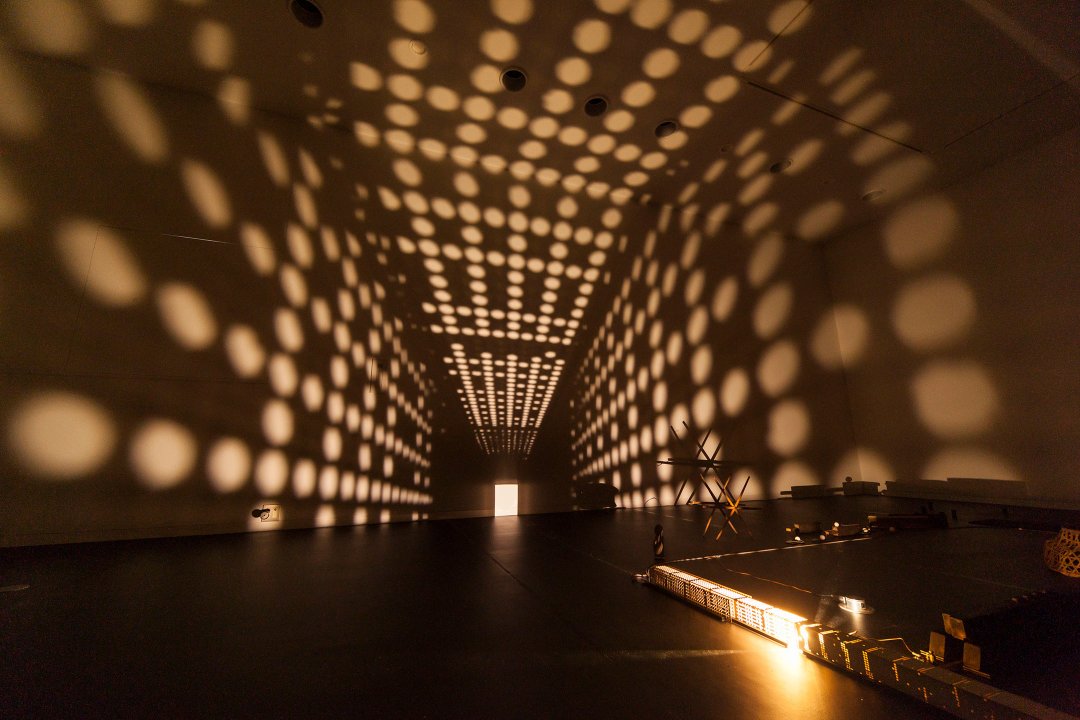

With the artists, we also had a list. Our perspective was to give them a single guideline as well, which was very straightforward – one artist has one room, and one room has one colour, that was part of the context. Some of the artists followed that very strictly, and others had an idea that we integrated quite well into the building, so most of the art pieces are well integrated into the architecture.

Clip “Walk way” Photo by ANZAÏ

Kawaguchi Tatsuo “Relation–Blackboard Classroom” Photo by Nakamura Osamu

Fabrice Hybert “Autour du Feu, Dans le Desert” Photo by ANZAÏ

Jean-Luc Vilmouth “Café Reflet” Photo by ANZAÏ *Echigo-Matsudai Satoyama Shokudo

Q: NOHBUTAI was the first architecture project that you realized outside of Europe. What was the significance of this experience for your career?

First of all, the ability to travel to Japan of course was fantastic, and during my studies I was already fascinated by Japanese architecture, which started with Ando, then later on Ito and Sejima, they had a kind of structuralist approach. To be able to visit some of these projects was wonderful, and I was also able to do a semester as a guest professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology with Atelier Bow-Wow, who were also doing work near Matsudai at the same time. We had come across their work through their housing projects, and it was great that they were part of it. I really respected what they were doing, and I met them there, so it started more friendships. And we also need to recognise the collaboration with the local partner, and how we were super lucky with our Japanese collaborator Yoshitaka. That made communication so much easier, and also all the little details to which he paid attention, and of course for his career it was good for him to help deliver that project.

NOHBUTAI didn’t lead to any other projects immediately, but there was a request for a facade project in Omotesando, for which there’s a nice story. The project manager came to Rotterdam, and while we knew he was coming, he had booked the flight to Rotterdam because he was not aware that the best way to fly to the Netherlands was via Schiphol. Instead, he flew from Tokyo to London, and then London to Rotterdam. He then proceeded to walk from the airport to our office during heavy snowfall, which told us something about perseverance and dedication!

But I think with architecture in Japan generally it can be difficult to get to do. Business development is more limited, because the approach from the client is more “We’ll call you”, but working in Japan itself is great, you’re treated really respectfully – when it comes to detailing, for example, they listen to you. My colleagues Jan Knikker and Hui Hsin Liao visited our building Gyre recently which we completed in 2007, and it still looks fantastic. For that project we had Takenaka, who were not only the local architects, but also the construction, data design, and built delivery companies, so to say, and partly the investor as well. Everything being contained in one company was intriguing, and Gyre was a big thing – reputations are important so it means you have to do it well, doing the very best you can to please the client. It’s always nonetheless a dream to work there, there’s still a lot of love for craftsmanship.

Q: How have you seen NOHBUTAI and the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale develop over the past 20 years?

Personally, I’ve been back once on holiday with my family, when we went to see it. But of course the collection of art pieces in the landscape is growing, so it’s a fantastic destination, and the fact that it has already been running for such a long time is a sign of its success, and becomes even more exciting with each edition. It’s simply too bad that it’s so far away, because otherwise I would come to see it every time.

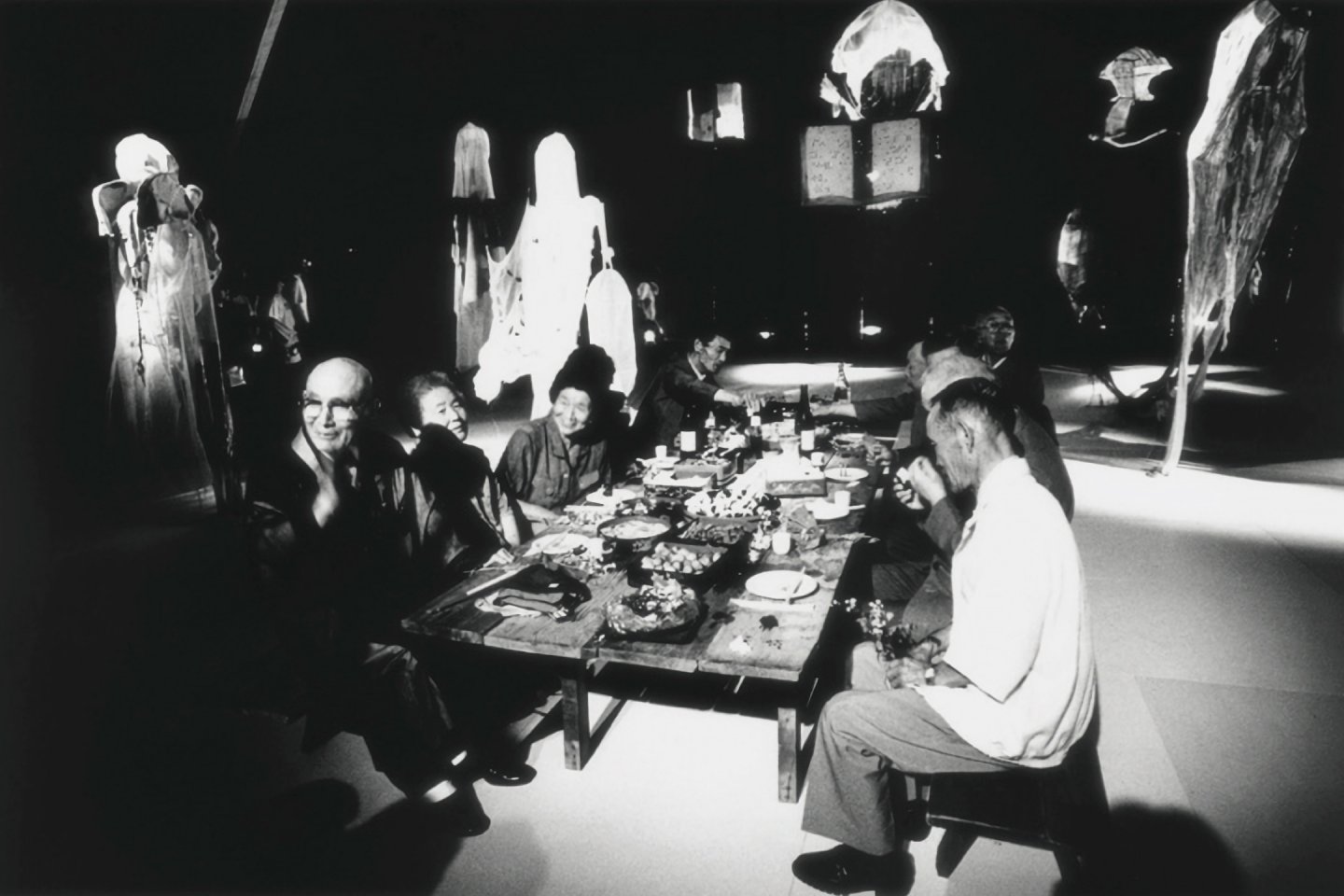

Photo by Nogawa Kasane

We look forward to seeing the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale and Art Field continue to grow in the future, to help support the community of Echigo-Tsumari and the broader Niigata prefecture.

PROFILE

MVRDV

MVRDV was founded in 1993 by Winy Maas, Jacob van Rijs and Nathalie de Vries. MVRDV is an acronym of the founding members’ surnames. Now, the three founding partners lead a dynamic and optimistic team of over 300 partners. Based in Rotterdam, Shanghai, Paris, Berlin, and New York, they have a global scope, providing solutions to contemporary architectural and urban issues in all regions of the world. (photo:©Erik Smits Jacob)

https://www.mvrdv.com/

Artwork 1.

Depot(2020)

(photo:© Ossip van Duivenbode )

https://www.mvrdv.com/projects/10/depot-boijmans-van-beuningen

Artwork 3.

Tainan Spring(2020)

(photo:© Daria Scagliola)

https://www.mvrdv.com/projects/272/tainan-spring