Thinking 21st century art in the world from Niigata

Echigo-Tsumari Art Field - Official Web Magazine

Artwork /

The Monument of Tolerance by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov

The Monument of Tolerance (2021)

Photo Nakamura Osamu

Artwork /

The Monument of Tolerance by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov

The Monument of Tolerance (2021)

Photo Nakamura Osamu

The Completion of “The Monument of Tolerance” — Kabakov’s Dreams Realised

Text and editing by Art Front Gallery

22 December 2021

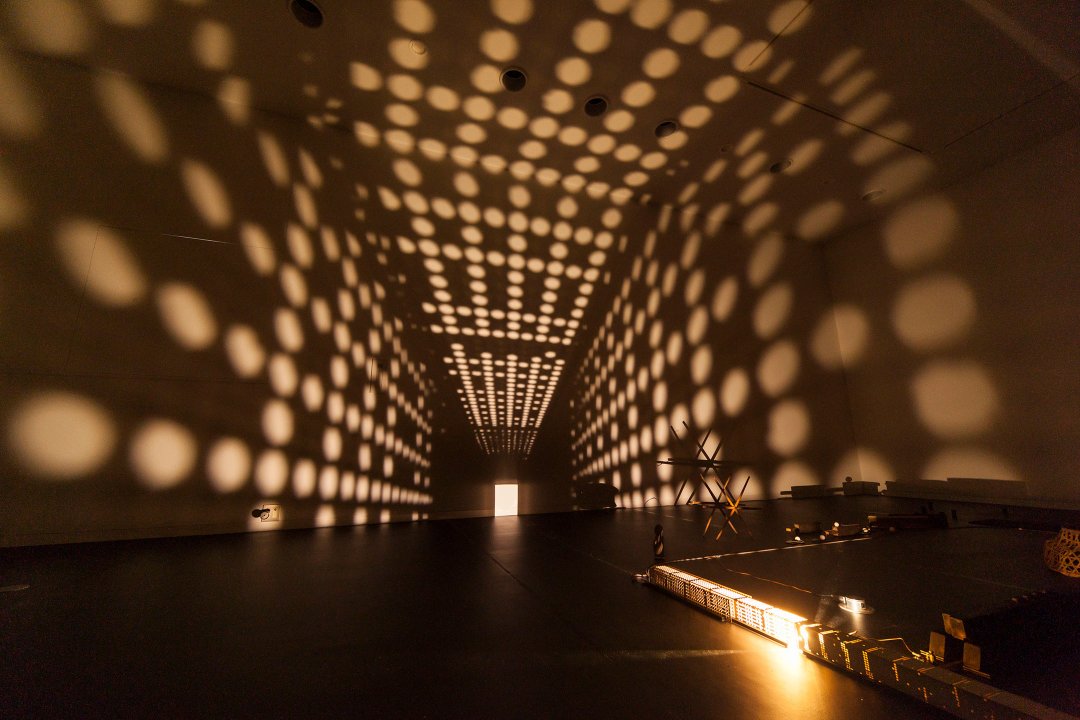

On 11 December 2021, The Monument of Tolerance by Ilya and Emilia Kabakov was completed, and a commemorative event was held to mark its opening.

The Kabakovs first participated in the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale in 2000, at its inaugural edition. Their work The Rice Field, which expressed the process of rice cultivation through poetry and sculpture, celebrated the labour and lives of the people of Echigo-Tsumari and has since become one of the defining works of the Triennale.

In 2015, The Arch of Life was created. From 2020, the project Kabakov’s Dreams began to take shape. In July 2021, four new works were unveiled at Matsudai Nohbutai, with one additional work presented at the Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art, MonET.

The Monument of Tolerance stands as the culmination of this process, bringing together a total of nine works—new and existing—to complete Kabakov’s Dreams.

Kabakov’s Dreams, Made Possible by the Pandemic

The Monument of Tolerance (2021)

Photo: Nakamura Osamu

The proposal for the Monument of Tolerance was first received from the Kabakovs on 9 June 2020, at a time when COVID-19 was spreading across the globe and lockdowns and states of emergency were being declared in rapid succession.

Conceived as the world became increasingly divided and the spirit of tolerance seemed to be eroding, the work was envisioned as: “a monument expressing human connection, a monument that encourages people to speak peacefully about their differences, their problems, and their concerns.”

The monument, whose light changes colour in response to the emotions—joy, anger, sorrow, and delight—of people both globally and locally, evoked for General Director Kitagawa Fram the words of Dutch historian Johan Huizinga in The Autumn of the Middle Ages, describing church bells that “at times proclaim sorrow, and at times joy.”

Although the artists and budget for the 8th Triennale had already been finalised, the decision was made to proceed with the production of this work.

Around the same time, in June 2020, the Kabakovs took part in the Instagram project Artists’ Breath, where they remarked:

“We are not surprised by this situation at all. Artists are accustomed to solitude. This moment is an opportunity to become even more creative, to make full use of our imagination, and to make this world a more beautiful and interesting place.”

These words reflect the Ilya Kabakov’s long experience of producing works “for himself” under the cultural restrictions of the former Soviet Union, with no prospect of public presentation.

The proposal for The Monument of Tolerance developed into a broader project to create an archive of the Kabakovs’ dreams—dreams sustained through adversity and the continued act of making—here in Echigo-Tsumari. Thus, Kabakov’s Dreams was conceived.

With Kono Wakana, a Kabakov scholar who also coordinated The Arch of Life, as curator; architects Toshimitsu Osamu and Tao Genshu as designers; and through extensive correspondence with the Kabakovs, the project steadily took shape.

In April 2021, it was decided that the Triennale scheduled for that summer would be postponed until the following year. Nevertheless, the project continued uninterrupted. Through collaboration with light artist Takahashi Kyota, the local Takahashi construction team, and many others, Kabakov’s Dreams was brought to completion.

Looking back, Kitagawa Fram reflects:

“It was precisely because 2021 was marked by the pandemic that this project became possible.

Profile

Ilya and Emilia Kabakov

Russia

Ilya Kabakov was born in 1933 in the former Soviet Union (now Ukraine) and lived in New York. From the 1950s to the 1980s, he worked officially as an illustrator of children’s books while continuing his unofficial artistic practice. In the mid-1980s, he relocated his base overseas and began presenting total installations recreating Soviet spatial environments at international exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale and documenta.

In 1988, he began collaborating with Emilia Kabakov (born 1945). In Japan, their major solo exhibitions have included The Life and Creativity of Charles Rosenthal (1999), Where Is Our Place? (2004), and Ilya Kabakov: The World Atlas — Picture Books and Original Drawings (2007).

In Echigo-Tsumari, The Rice Field (2000) and The Arch of Life (2015) were installed as permanent works.

In 2008, Ilya Kabakov received the Praemium Imperiale.

The Rice Field (2000)

Photo: Nakamura Osamu

The Arch of Life (2015)

Photo: Nakamura Osamu

A Monument That Communicates with the World, Standing on Joyama

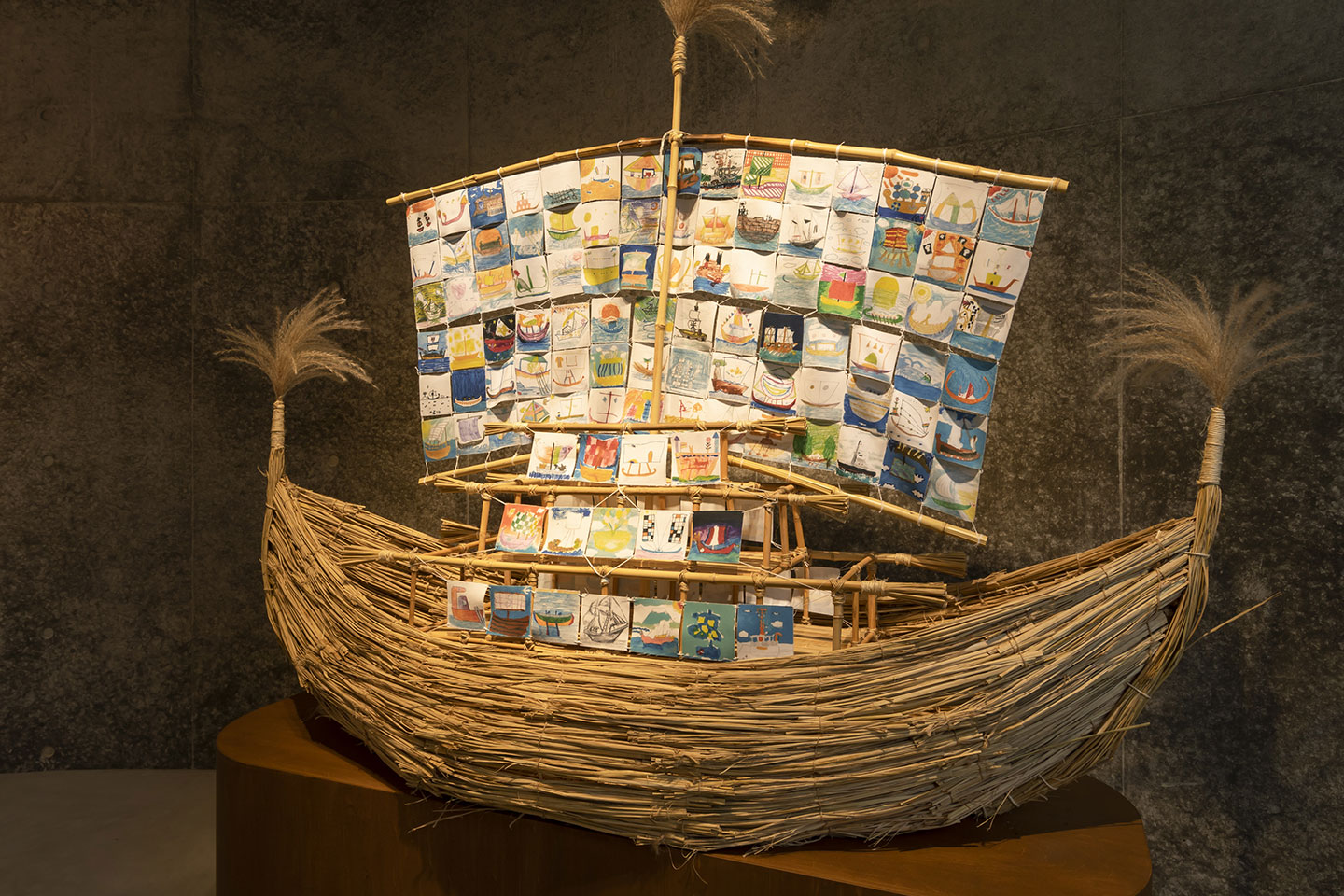

The base of the Monument of Tolerance functions as an exhibition space. On display are the five sculptural figures from the Arch of Life, six reproduced oil paintings depicting angels not realised in sculptural form, and a model of the Ship of Tolerance, a project the Kabakovs have been developing since 2005.

The Ship of Tolerance (2021) — model display

Photo Nakamura Osamu

Reproductions of oil paintings from the Arch of Life displayed inside the monument

Photo: Nakamura Osamu

The Ship of Tolerance is a sister project to the Monument of Tolerance. Using a ship designed by the Kabakovs, sails are created from drawings by children from around the world. Through creative exchange, the project aims to foster learning about respect for diverse cultures and ways of thinking. To date, it has been realised in Egypt, Italy, Switzerland, the United Arab Emirates, Cuba, the United States, and Russia.

The interior of the monument is intended not only as an exhibition space, but also as a place for listening to music and quiet contemplation. The surrounding area will be developed as a small park, offering a place for rest and conversation.

The Ship of Tolerance — realised project

Photo: Daniel Hegglin

At the opening ceremony, Tokamachi Mayor Sekiguchi Yoshifumi, Chair of the Triennale Executive Committee, remarked:

“With the birth of the Kabakovs’ third work at Matsudai Joyama—symbolic of the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale—it feels as though we are entering a ‘Kabakov World’. I am excited to imagine people across Japan and around the world encountering this body of work, in which the Kabakovs’ spirit has come to fruition, at the next Triennale.”

Kitagawa Fram added:

“This monument is like an experimental laboratory communicating with the universe, and at the same time, like a sanctuary. As people stroll around Joyama, I hope they will feel drawn to it, thinking, ‘What is that curious building?’”

From New York, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov sent the following video message:

“We had dreamed of creating this sculpture for a long time. And finally, with the help of our friends in Japan, it has been realised here in Echigo-Tsumari—far beyond what we imagined.

The Monument of Tolerance is not a project limited to Echigo-Tsumari alone; it is a universal project. We hope it will bring light, hope, and dreams, becoming something more interesting, more peaceful, and meaningful for people around the world. We offer our heartfelt thanks to everyone who helped make our dream a reality.”

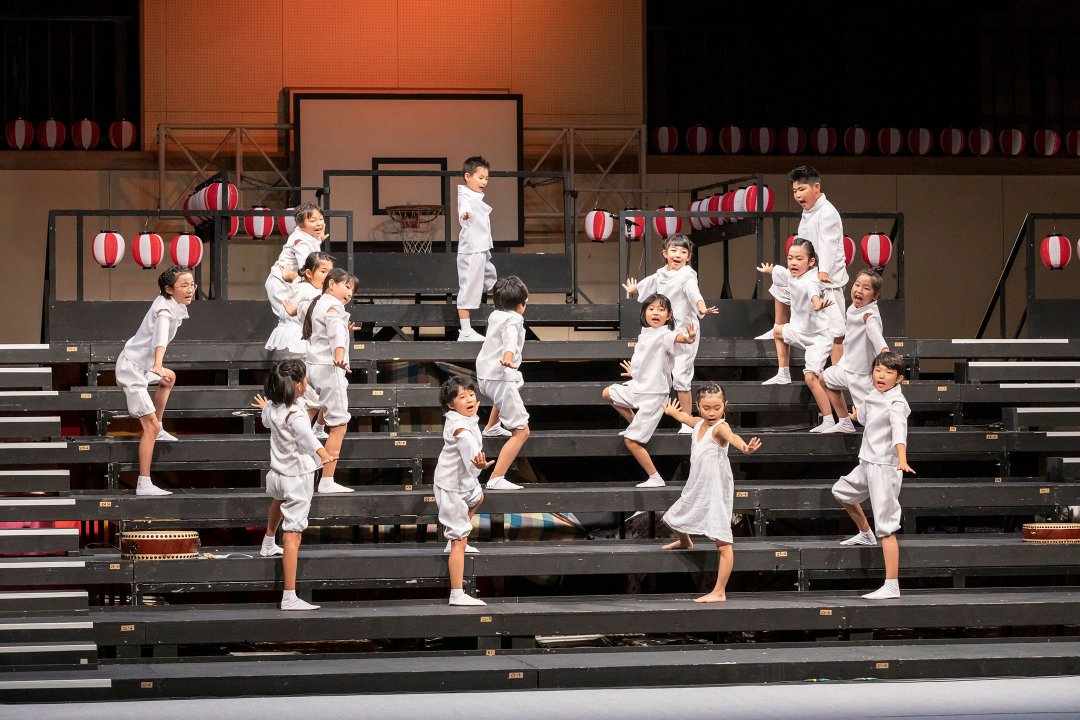

Symposium: Kabakov’s Dreams — Art for Survival

To commemorate the opening, a symposium titled Kabakov’s Dreams — Art for Survival was held. Local residents, Russian nationals living in Japan, and participants from across the country gathered, filling Kawaguchi Tatsuo’s Relation – Blackboard Classroom at Matsudai Nohbutai with a palpable sense of celebration.

Participants in the symposium

Opening the symposium, Kitagawa Fram stated:

“In today’s world, site-specific art rooted in its own space and time is becoming increasingly important, as encounters between people of different backgrounds and generations mediated by art take on greater meaning. This symposium, held to mark the completion of “The Monument of Tolerance”, offers an opportunity to reaffirm the Triennale’s guiding principle: ‘Our feet on the ground, our eyes toward the wider world.’”

Professor Kono Wakana (Waseda University) traced the Kabakovs’ journey from Ilya Kabakov’s birth in 1933 through to their encounter with Echigo-Tsumari, introducing the process through which nine works came to be realised in the region. (Click here to read another contribution by Professor Kono when MonET and Matsudai Nohbutai re-opened in July 2021.)

Professor Suzuki Masami (Niigata University) and a specialist in Russian culture, spoke under the title Kabakov and Unofficial Art, addressing Ilya Kabakov’s activities during the Soviet era. Quoting from Kabakov’s book Notes on Unofficial Life in Moscow in the 1960s–70s (1999), Suzuki brought to light the extraordinary energy of artists who, despite living under strict cultural control and in an atmosphere of profound constraint, gathered night after night in studios and private apartments.

There, they talked and argued at length, shared drinks, sang songs, and read poetry aloud, allowing what might be called an “underground culture” to take root and flourish. What emerged was not only a collective vitality, but also Ilya Kabakov’s own figure as an avant-garde artist deeply embedded in this milieu—someone who actively engaged with a wide range of artists, poets, and musicians, and who participated enthusiastically in experimental performances and collective actions.

Suzuki quoted the following passage from Kabakov’s book:

“Every night, as we gathered to drink, how many ideas, events, and problems must we have discussed. (…) There was a profound sense of happiness—speaking with excitement about new occurrences, sharing something with one another, and debating. This was the joyful atmosphere that, throughout that entire era, allowed us to breathe, to exist, and to work.”

Art critic Kuresawa Takemi (Tokyo University of Technology) spoke about how, under the conditions of the Cold War, Ilya Kabakov encountered and absorbed developments in Western art while living in the former Soviet Union, and how his work came to be recognised and evaluated in the West.

During the so-called “Thaw” of the 1950s, Kabakov was exposed to advanced artistic movements from the West. From that point on, he responded keenly to Western intellectual and artistic currents—such as cultural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss’s concept of the mytheme, as well as conceptual art and appropriation art—incorporating these ideas sensitively into his own practice. Through this process, he came to be recognised as a leading figure of Moscow Conceptualism.

After 1985, as perestroika made it possible for artists to work internationally, Kabakov began to expand his activities abroad in earnest. Establishing his base in the West, he continued to produce what he termed “total installations”—works that retained, with particular intensity, elements rooted in the social and spatial conditions of the former Soviet Union, which remained central to his artistic identity.

Kabakov’s distinctive approach, which sought to transform two-dimensional space through installation, is characterised by a material directness combined with a powerful narrative quality. His work embodies, at a profound level, both of the major currents of twentieth-century art: abstract expression and conceptual art. For this reason, Kabakov is highly regarded as an artist “standing at the crossroads of East and West.

Finally, a question was raised from the audience as to why the Kabakovs has developed such a deep attachment to Echigo-Tsumari, and how their encounter with the region has influenced and transformed their artistic practice.

In response, General Director Kitagawa Fram said:

“The Kabakovs chose Echigo-Tsumari because they genuinely believe this is a good place. Above all, it is because the people involved here work with such commitment. The meaning of a work is, of course, important—but even more so are the process through which it is made, and the system that sustains and operates it. Creating art is never easy. There are struggles with administrative systems, and many obstacles to overcome. Yet even under difficult circumstances, there exists within the people here a place where art can be incubated. That is Echigo-Tsumari.”

Kono Wakana then added:

“After moving to the West, the Kabakovs began to feel the limits of continuing to work solely with themes drawn from the Soviet Union. It was through their encounter with Echigo-Tsumari that they created ‘The Rice Field’, a work centred on the theme of labour. I believe it was a piece through which they sensed new possibilities—possibilities that could connect to any place in the world.”

Russia, Connected Across the Sea

Following the symposium, a reception was held at the Echigo Matsudai Satoyama Shokudo, featuring Russian cuisine and music.

Opening reception at Echigo Matsudai Satoyama Shokudo

Russian songs and music by Evgeny Uzhinin

In Echigo-Tsumari, alongside the Kabakovs’ works, Francisco Infante’s Point of View (2000) can be found at Shibatoge Onsen; Tanya Badanina’s Reminiscence – Vague Memory is installed at Nunagawa Campus; and in the 2018 Triennale, Alexander Ponomarev’s Antarctic Biennale – FramII was presented alongside a symposium.

Niigata is home to a Russian consulate, and Russia has long been one of Japan’s closest historical neighbours. Yet today, many still perceive it as “near, yet distant”.

At the next Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale, an exhibition from Moscow’s Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts is scheduled to be held at MonET. Toward a richer relationship with the people of neighbouring Russia, an important step has been taken.