Thinking 21st century art in the world from Niigata

Echigo-Tsumari Art Field - Official Web Magazine

Staff / From behind the scene of Echigo-Tsumari

Learning from the community: handiwork in winter to pass onto future generations - A report on "learning with KITAGAWA Fram"

27 January 2021

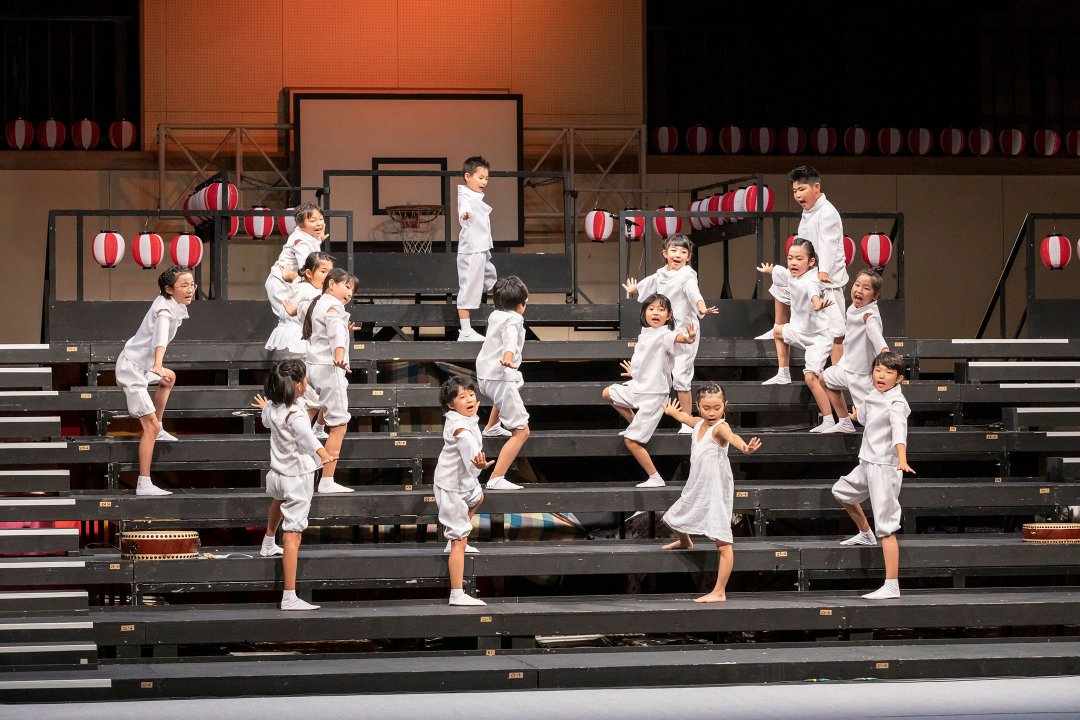

“Learning with KITAGAWA Fram” is series of learning opportunities comprised of lectures and two workshops on site led by KITAGAWA Fram, General Director of ETAT to learn how the regional festival is operated. In the middle of December as snow started to fall, various participants including kohebi members and local volunteers gathered at Sansho House in Kotani village in Matsunoyama area to participate in two on-site workshops “making shimenawa (laid rice straw rope used for ritual purification in the Shinto religion) and yacho (wild bird)-kokeshi” which aim to deepen the appreciation of local rituals in winter and their culture.

Rituals in winter that have been passed onto for generations in community

自然の流れにそって生きる集落の暮らしに、季節ごとの風習があります。秋の稲刈りが終わったら、雪に備えて雪囲いをして、食料を貯蔵。そして12月に入る頃には本格的に年越しの準備が始まります。どのお宅も大掃除と煤払いをして家を綺麗にして、神棚を美しく飾り、お供えやごちそうを準備して、年神様を迎えるのです。しめ縄作りは、そんな冬の伝統的な生活文化のひとつです。

Mr AIZAWA Ryo from Kotani village was the lecturer to talk about the culture of the village. AIZAWA is a Niigata-prefecture certified instructor of exchange experience and very knowledgeable about culture, history and nature of the region.We were privaledged to learn a lot of important stories from him.

三省ハウスの集会室には、小正月の行事「どんと焼き」の様子が展示されている。神主役を務めたのも亨さん。

Shimenawa for the new year has been mass-produced by now. While the average size is the one reduced to fit into the contemporary house, it is still hand-made in this region and different regions have their own ways to make it.

“When starting a primary school, children learn how to nawanai (make a rope). By the age of ten (4th grade at primary school), they can make a pair of zori (straw sandals) and even a pair of long-boots before graduating from the primary school. We used to make anything from necessary tools to items for festivals when we came back from school. Straw was essential and precious item for self-susstaining life. Everyone regardless of age was able to handle straw.”

From what Ryo told us, we could feel that how all these means and techniques that were developed as they lived made everyday life rich.

Some participants had been visiting Echigo-Tsumari every month since joining one of the on-site workshop in summer. They would feel the life of the village which change in accordance with different seasons as they saw that the rice they harvested in late summer are treasured and used in winter. What was also impressive about stories that Ryo told us was a unique end-of-year ritual of Matsunoyama.

“Around here, we celebrate the end of the year in the noon of 31 December. During the Nanboku-chō period (1336 to 1392), this area was governed by local Gōzoku (wealthy family) and flourished with Murono-jo castle in the centre. However, since the bitter experience of the castle fallen during the evening feast on one new year’s eve, people in this area celebrate the year-end during the day and lock the door in the evening to welcome a new year.”

We worked in the friendly atmosphere as we learn such distinctive culture of new year in this community. Ryo took no time to make a beautiful rope by twisting straw using his hands and feet.

On the other hand, we struggled to even start the process. What does “nawanai” mean? Why they fall apart as we twist them together! So many questions were asked by ten participants.

Thanks to kind guidance, we somehow managed to make a rope while wishing we had two more pairs of hands and feet although we were covered by straw all over the body.

Techniques in life is part of art

Artists who create artwork for the festival also visit Echigo-Tsumari and build relationship with local people to learn about the history of the place. During the production process of their works, these handiwork in the community could inspire the artists or result in collaboration as they introduce traditional local techniques. For example, Cai Guo-Qiang introduced the making technique of shimenawa into his work “Penglai / Horai” for ETAT2015 and various straw objects created in collaboration with local people were presented along the pond in KINARE.

"Penglai / Horai"by Cai Guo-Qiang / photo of part of the work by NAKAMURA Osamu

Because this region is filled with distinctive and rich culture, it would contribute to the production of diverse artworks which secretly hold a hint of element of Echigo-Tsumari. Such thought would make the visit ti these artworks more exciting.

Things to pass onto over long period of time

The next thing we learnt was “yacho (wild bird) kokeshi“. It is a local craft so typical to Matsunoyama where lots of wild birds inhabit. While those who have visited Echigo-Tsumari may have seen them on display at Matsudai station on Hokuhoku Line or Sansho House, there haven’t been an opportunity to contemplate how they are made and what kind of story they have.

Yacho kokeshi was originally created as a hobby by a man running an inn in Matsunoyama about 60 years ago in 1950s. It was spread in the community as one of the means to earn money at home when they couldn’t do farming because of landslide or heavy snowfall and yacho kokeshi were sold as a souvenir of Matsunoyama

Each material is made by different people ranging from dyed cotton for its body, wires, colours threads and real feathers of bird – all of them are now so precious and difficult to find. Even the production process is divided into different phases to different people each requires high and detailed skill and there are only five people who can make yacho kokeshi now.

FUKUHARA Natsuki, the lecturer of this workshop has been investing effort in learning and handing down this disappearing technique to future generations. “YouMyHeart Matsunoyama”, an agent who put us in touch with FUKUHARA organises this workshop so that yacho kokeshi will be known to more people.

While each of more than 20 different kinds of wild bird has its own production process, what we made was “akashobin” (ruddy kingfisher), a symbol of Matsunoyama with distinctive singing.

FUKUHARA told us the difficulty of passing the technique of making yacho kokeshi onto next generations as follows:

“As we don’t do one thing throughout the year. We are busy with farming from summer to autumn and we would start making yacho kokeshi after finishing harvest. However, we tend to forget how to make it during the time we don’t engage with making. So it takes years to become someone who can make it properly.”

When you actually try to make it, you realise that it is not something one could acquire in short period of time as each process requires skills such as subtle force adjustment.

After spending approximately three hours, we managed to complete akashobin kokeshi. Although they are not in perfect shape, they are adorable with individual unique expression.

Passing on the local culture to next generations

Winter handicraft deeply related to a climate (fudo) of this place, which has been passed onto the next generations, because this region is closed for severe winter. Rather than using excuses such as “change in lifestyle” or “lack of people taking over”, various engagements such as knowing, experiencing, and expressing could contribute to pass the dissapearing culture onto the next generation.

In the collections of students’ work prior to the Sansho House closure, we could see children learning how to make straw crafts from local people. Remembering memories of different time overlapped in the same space of the Sansho House, I was once again determined to continue making such time through art festival and volunteering activities.

ETAT, Tourist Department, Tokamachi-city Council / Chiiki-Okoshi-Kyoryokutai

Sato Ayu

information