Thinking 21st century art in the world from Niigata

Echigo-Tsumari Art Field - Official Web Magazine

Feature / Director's Column Vol.3

Twenty years of changes, from the early phase when the region was opposed and the festival was postponed

Fram Kitagawa ("Art from the Land" editor-in-chef / ETAT General Director)

ETAT is open to many people. When many people gather in one place, it is natural for there to be as many backgrounds and opinions as there are people. What kind of space has ETAT tried to become? Kitagawa, who has been General Director of the festival since its beginning will answer to that question.

Text by UCHIDA Shinichi / Edit by MIYAHARA Tomoyuki, KAWAURA Kei (CINRA.NET editorial team) / Photo by TOYOSHIMA Nozomu / Translated by Miwa Worrall

06 January 2020

As a place open to diverse people

“Humans are part of nature” is the basic principal of ETAT. In this series we have already introduced how the festival has taken as its stage this distinctive place called Echigo-Tsumari where humans and nature co-exist, and how it has opened this up to so many people. Here, we would like to look at the relations between ETAT and those who are involved.

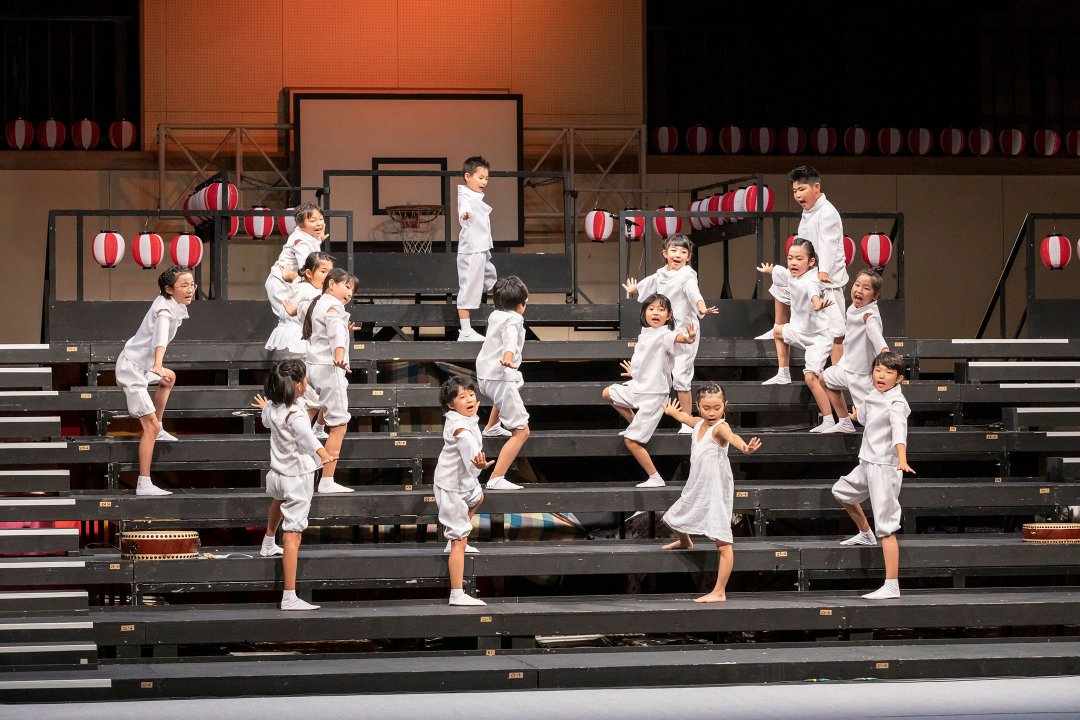

Echigo-Tsumari Art Field welcomes visitors to different seasonal programs throughout the year. The highlight of these activities is the Triennale that takes place once very three years. It has been expanded from its beginning in 2000 to its seventh iteration in 2018, encompassing 379 artworks presented across 102 villages in the region and receiving 548,380 visitors. (1)

(1) Tokamachi Biyori (Tokamachi Tourism Associations’ website) shares these data from previous festivals as well as the official report of each festival online.

While the fan base of contemporary art has expanded since the start in 2000, its proportion in the overall picture is still limited. Some people may visit Echigo-Tsumari thinking “Tokyo Disneyland is fun but I don’t mind spending two or three days at ETAT for a change”. Young people in their teens and twenties come with their friends whereas other generations bring their children or grandchildren. The data also shows that a significant number of working women in their late thirties and older visit here. Some try to find the cheapest accommodation possible whereas the other would choose to spend on luxury options. The number of visitors from abroad has been on the increase in recent years.

As a result, the festival operation team faces challenges. How should we best present unconventional projects to an audience that is diverse and not just aficionados of contemporary art. Any single artwork or project may attract a diversity of views. However, paradoxical as it may sound, I believe there is meaning in such mixtures, as we seek out common ground within the differences. If we limit our audience to those who only appreciate contemporary art, for example, things will become simpler to some extent. Because of the diversity, there is a potential to create various things which, I believe, presents challenges we could engage with.

“The Last Class” by Christian Boltanski and Jean Kalman, 2006 (photo by Takuboku Kuratani)

Exchanging yells for how to live

One of the reasons why Echigo-Tsumari attracts people is the energy of the placecoming from themultiple layers of nature, history and life. Things begin to look more interesting and compelling through artworks that are born in such a place. I do believe that is what this place has. Many of the works featuring local activities and being in that place and not anywhere else, makes a big difference. That is why each individual can discover the unique value of each work for themselves.

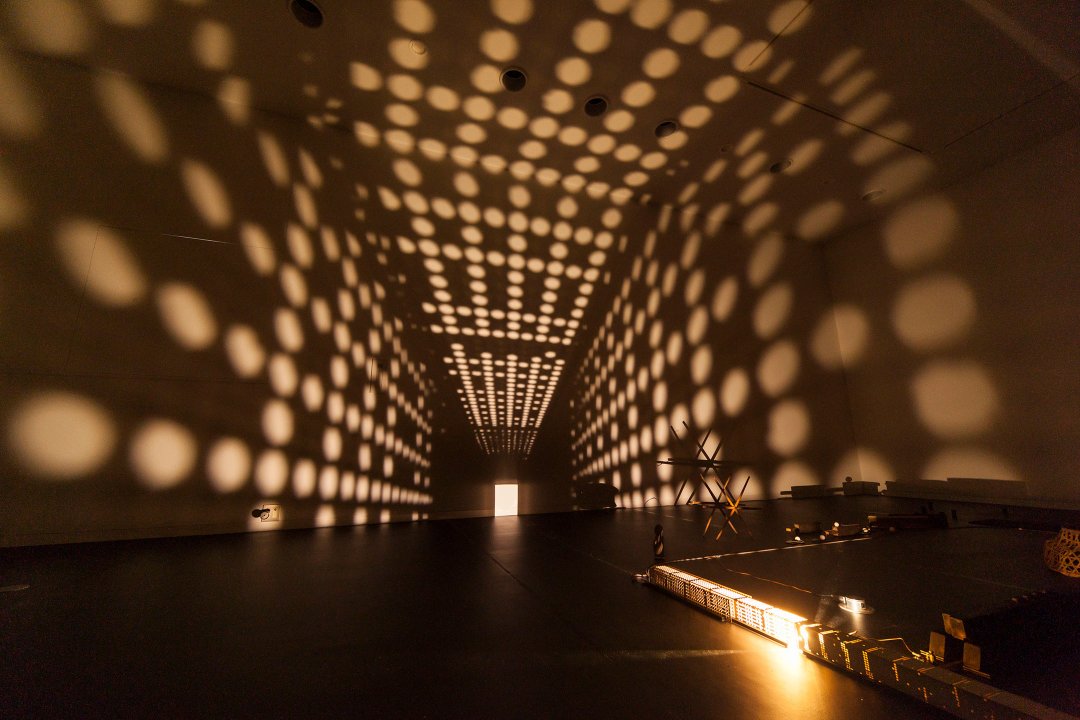

A good example of this is “The Last Class,” (which I introduced in my last article), an artwork by Christian Boltanski in collaboration with Jean Kalman, an internationally acclaimed stage lighting technician. It is an installation made of materials that are familiar to life in Echigo-Tsumari, such as straw and snow shieldspresented in the spaces of a closed elementary school, using naked electric bulbs hanging from the ceiling.

On the whole, the installation consists of simple elements. However, the materials mentioned above and random things relating to the school which were brought in by villagers fill the space with the memories and spirit of the people who were once there. Boltanski visited the site in the midst of winter when developing the idea for the work and experienced the harsh life of the locals, having had to clear two to three meters of snow. Such experiences have also been reflected to the completed work.

I should note here that I appreciate Western art and I have grown up with this endowment. However, from the very beginning ETAT has had no intention to simply follow this. It is not easy to conclude which one is more attractive or valuable when comparing an artwork by Picasso and an African mask.They are both interesting in their respective ways. That is why ETAT has included “art in life”such as culinary culture, ikebana, and ceramics, in addition to contemporary artworks by domestic and overseas artists, as expressions to engage with the region. People with different sets of values and cultural backgrounds gather here from all over the world and exchange their respective views, using words like “In my view…” or “my feeling is…” – I regard such a phenomenon itself as also a richness.

Changing the perspective slightly, we have no choice but to live a reality in which the development of capitalism and the global economy are leading to environmental destruction, widening disparities and the advance of an excessive efficiency. However, whether you are living in a big metropolis or in a regional city, you may still wonder if something is wrong or ask yourself if everything is alright. How to grasp what is going to emerge in the coming era and what do about it? I could feel that those who are consciously asking these questions are interested in ETAT – not just individuals but also companies such as Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd. (3)

3. Ryohin Keikaku Co., Ltd, known for MUJI brand runs Muji Campground Tsunan in Tsunan-town, Niigta where ETAT is staged.

As has been already mentioned above, many working women in their late 30s and older are among the visitors to ETAT. They can be described as true opinion leader in contemporary Japanese society. Many of them take the question of how to live seriously as they face difficulties balancing work and family (although it is supposed to be an issue that should be engaged in regardless of gender.) They have to deal with the elderly, children and their own careers. I think about the significance of their existence. It is just my feeling but these women connect instantly beyond their differences when they encounter each other at ETAT.

Generally speaking, I do hope that ETAT and these people, while holding different positions in society, would still be able to build a relationship in which they could “exchange yells” with one another.

“Where Has the River Gone” by Yukihisa Isobe, 2000 (photo by Osamu Nakamura)

Seeking what can be shared beyond differences in opinion

Naturally, the relation between the local people and ETAT is important. The origin of ETAT was the “Riso Plan,” a plan by Niigata Prefecture to revitalise community. The history of Echigo-Tsumari goes back more than 1500 years and it was once a region that supported Japan through rice production. However, the region faces the challenges of depopulation and ageing due to the concentration of population in the big cities and changing industries as a result of shift in agricultural policy.

Although ETAT was proposed as a means to find what can be done to support this region, the doubts and opposition amongst local people towards such an unfamiliar proposition were strong, and the first festival, set for 1999, was postponed. After long discussions, we managed to launch the first iteration of ETAT in 2000 and since then the meaning of ETAT for the local people has gradually evolved through ongoing discussions and exchanges with artists and visitors.

Meanwhile, I have come to realise one thing as I have continued my endeavour. While depopulation, ageing and the decline of industry exist as pressing local challenges, what is felt most painfully for people who have been living in this region is losing a place to make use of their wisdom and skills. For example, a place in the mountains where you might find the best sansai(mountain vegetables) that you would keep as a secret even from your family members, or the distinctive skills and wisdom of farming and clearing snow which they have been routinely engaged with.

When the festival asks these local people for help on something that they can utilise their experiences, they genuinely seem pleased. As mentioned, Boltanski used straw for “The Last Class”, and I would imagine he was very impressed when he saw the way locals bundled the straws. That was the distinctive skill of the region and mastery of those who make things.

When you see an artist going through trial and error and working hard, those who have previously regarded artists as people who deal with things that are beyond their comprehension begin to appreciate or empathise with them. “The Seat of Rain Spirit” (2000-2009) by Takamasa Kuniyasu is a large scale work assembling bricks and timber from forest thinning. Local seniors who watched the artist working silently and diligently from a distance at first eventually provided their expertise as a team and helped complete the work.

“The Seat of Rain Spirit” by Takamasa Kuniyasu, 2000 (photo: ANZAI)

I also have strong memory of “Where the River Has Gone” by Yukihisa Isobe (2000 / re-installed in 2018). The artwork expressed the changing flow of the Shinanogawa River from a century ago using 700 yellow poles with flags. The project began with explaining the work to each of the land owners seeking their permissions. It wasn’t long before one of the local residents who had opposed the project at first gave us the advice “that it is windy around here and the wind changes directions from time to time – so it would be interesting to add flags to the pole”.

While this relates back to the principal concept of the festival that I mentioned at the beginning of this article, the more things that have been scientifically elucidated, the stronger I have come to believe that humans are part of nature. Each individual physiologically engages with an external environment through what connects them to nature. In other words, 7.5 billion different physiologies co-exist. As a matter of course, it is best to consider something based upon the assumption that there will always be differences that can never be unified. And I believe that what plays an important role here is the presence of an existing community, and that the art has high compatibility with the places where we implement our projects.

Profile

Fram Kitagawa

"Art from the Land" editor-in-chef / ETAT General Director

Born in 1946 in Takada-city (current Joetsu-city), Niigata, Japan. Kitagawa has been General Director of ETAT (launched 2000) since its preparation phase to date. He is also an editor-in-chief of webmagazine, “Art from the Land: Thinking 21stcentury art in the world from Niigata”.